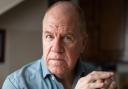

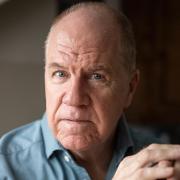

Former medic for the Special Boat Service, Steel Johnson from Plymouth, has swapped the Royal Marines for magic. This is his story, writes Fran McElhone

Steel makes the card I just picked disappear, then reappear, then makes it change from blue to red. Then he proceeds to fan out his deck, and turns them all red. Then he turns them back to blue again. A slick illusionist, an adept trickster, a sleight of hand virtuoso, and, if you were unconvinced before, Steel will have you believing in magic.

But Steel, real name James, wasn’t always a magician. For the last 10 years he’s been a Royal Marines Commando, spending the last year-and-a-half of his service as a medic with the country’s elite amphibious fighting force, the Special Boat Service (SBS).

Prior to his decade in the Corps, he was an infantryman in the Army for several years, which included a tour of duty in Iraq aged 20. Sandwiched between the Army and Marines was a year travelling the world.

It was his deployment to Afghanistan in 2008-2009 with 45 Commando which saw him witnessing friends endure horrific injuries in the most unimaginable of circumstances and demonstrating incredible fortitude and selflessness. His experiences in the desert, coupled with the sadness of losing his father to cancer, led to a period of deep reflection and a decision to follow his heart and become a magician.

The 32-year-old Lance Corporal has been practising magic for around six years now, performing at weddings, charity dinners and Corps’ functions.

“Iraq was why I left the Army,” Steel admits. “But you soon forget how bad a situation is and while I was travelling I had a constant itch to join the Marines.”

Within a few months of passing out at the Commando Training Centre in Lympstone, Steel was in Helmand Province fighting the Taliban. “Afghanistan was a really rough time,” he tells me, starting to shift about on the sofa as he taps into a difficult thread of memories. “It was relentless, there were a lot of casualties,” he continues. “The first one happened after about three weeks of getting out there; we were out on a night patrol and when we rounded a corner the guy in front of me stepped on an explosive and lost his leg. We carried him back to camp. I’d been up in front of him until just before that point.

“Then on New Year’s Eve we were out on patrol. It was a peaceful sunny day. You’d never think you were in the middle of a war zone and then, suddenly, we heard a massive explosion. They are so loud they’re deafening, everyone drops to one knee and then it just rains mud and debris.

“Then we heard someone screaming. I ran down the line of lads and realised that our point man with the metal detector had been hit in the explosion whilst going up the other side of a wadi.

“He was peppered with shrapnel and lost bits of his arm, but because of his day sack, and that he had been waist deep in the ditch, he was otherwise intact. As I ran to him I remember looking down and thinking, whose Bergen is that? And then I realised it wasn’t a day sack, it was our section commander Elmsy.”

Steel ran into intense enemy fire and the vital first aid he administered saved his friend’s arm from amputation. “I remember picking him up by his body armour and jumping back into the wadi before hauling him back on my shoulders to get out of there.”

Steel returned to the fight and helped bring Elmsy back on a stretcher. Sadly he did not survive his injuries.

The memories of theatre began to get to him in the years after that. In 2012 he was posted to Royal Marines Barracks Chivenor in North Devon, and 2013 proved another devastating year when his father died of cancer, 10 weeks after his diagnosis. Despite battling his grief, Steel was selected to be a medic for the SBS, based out of Poole: selection criteria includes being fitter, stronger and sharper than a regular commando. And be capable of parachuting out of a plane, 28,000ft high into an insurgent dominated zone. As a medic, the idea is to be able to facilitate prolonged care in remote locations under extreme and hostile conditions.

In the years after Afghanistan, Steel, who grew up in Yorkshire, found an inner peace through yoga and surfing the Devon waves, and magic.

“I had two sides to me; I was still a keen bootneck, but then the struggles I’d been through led me to become more philosophical about life,” he says.

Entirely self-taught, Steel is a fluid sleight of hand magician focussing on cards and close-up table magic, but he also works with fire, fruit and other objects.

He uses his nickname Steel Johnson, given to him by his comrades for his part in saving his friend, as his stage name. His business name, Timeless Deception has equally touching roots; “Someone said to me, time doesn’t exist, but I was like, my sergeant seems to think time exists! When my dad was ill, time became so precious, my dad and myself and my two brothers had a pocket watch engraved each to signify this. So that symbolism is important to me.

“People used to say to me, that every time I talked about Afghan, I’d get really fidgety, so I don’t know if I was channelling that energy into the cards or that subconsciously I was using magic as a release,” he continues. “I actually loved magic as a child but stopped doing it because I thought it was geeky and I wanted to be cool!” Steel laughs and tells me about the assembly he and his brother performed at where Steel made a glass disappear.

“I set up a table on Croyde beach one afternoon and think I made about three pounds because I didn’t want to go up and bother people!” he laughs, adding that it was during a surf trip with injured marines in Cornwall that he was spotted and invited to perform his first professional gig at a nearby beer festival.

“Things just took off from there by word of mouth,” Steel says. “I always have a pack of cards in my pocket. People ask me if I do it to attract girls, which kind of annoys me really, because I’m passionate about magic and very professional. And I hope I don’t need magic to attract girls!”

Steel starts describing his idea for a mobile cards and cocktails van, and a trick involving turning water into wine. It all sounds really cool, not at all geeky, and lots of fun, and I’m left feeling that there really ought to be more magic in people’s lives.

“When I’m performing magic, and I get people staring in awe, I just think that for those few moments they can forget about any problems they may have and just be absorbed in the magic,” he adds. “So for me, magic is about that break in reality and creating positive energy and enjoyment for people and making people smile. And that gives me such a buzz.”

Visit timelessdeception.co.uk